How the Neuroscience of Decision-Making Influences Moral Choices - for Better or for Worse

Growing up Catholic in a post 9/11 world, I was exposed to many beliefs that I now recognize quite simply as fear, judgement, and contempt. Yet I can still remember clearly all the reasoning used to justify these feelings.

It’s not only commonly taught by religious groups (both implicitly and explicitly) that “the other” is dangerous in some capacity, whether it be an immigrant or a queer couple, but this teaching is also instilled by society at large. Time and time again, I was exposed to lists of reasons on TV or on posters made by conservative and/or religious individuals explaining why these things are wrong. It was sometimes easy to accept this logic at face value as a kid.

But at the end of the day, I didn’t feel as though these things – or people – were truly immoral. My emotions didn’t align with the intensity of the messages I was absorbing. Though I may have experienced discomfort at times because of these indoctrinated beliefs, I never felt disgust or anxiety. I didn’t experience the same physical reactions that I did in response to legitimate crimes like assault, for instance. At this young age, I was confused because I had seen Muslim families laughing over dinner in restaurants just like me; I had seen queer couples playing hopscotch with their children at the park; I didn’t feel threatened. Despite the “logic” being shouted all around me, my emotions had the final say: this “other” wasn’t as bad as so many people were making it out to be.

What processes in the brain result in differences in morality? What is the relationship between emotion and logic? The answer lies in the neuroscience of decision making, including moral decision-making: what we decide is acceptable or unacceptable.

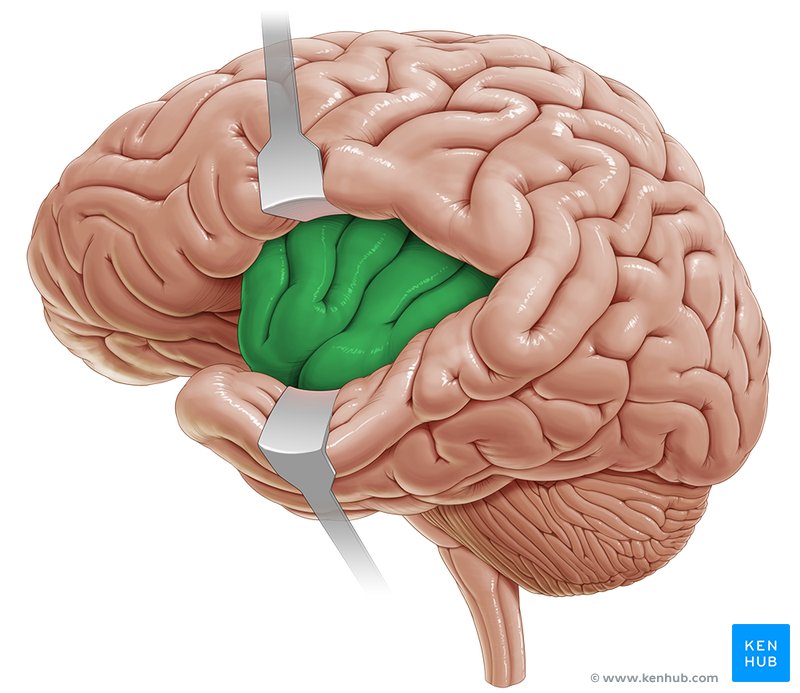

Some of us believe that we’re capable of making purely objective decisions without emotions “getting in the way,” that we’re able to separate our feelings from reasoning when we need to. However, according to neuroscience research, the ability to disconnect the two would require the severing of hundreds of millions of neurons. Structural brain mapping reveals extensive wiring between the rational and emotional centers in our brains. The prefrontal cortex, which is involved in executive functioning and reasoning abilities, often suppresses the amygdala and limbic circuitry (regions responsible for emotions).

This inhibition keeps us from always acting out our emotional urges and making impulsive decisions. We can stop ourselves from overindulging on junk food, or we can choose to stay calm in stressful situations instead of lashing out in anger. But, contrary to popular belief, the communication works both ways: the emotional centers regularly inform the prefrontal cortex, and this input is crucial to the decision-making process regardless of whether or not we’re aware of it. There is no way to “quiet” one region or the other – unless, of course, the brain is injured. This would be the fate of a certain man named Elliot.

Elliot was your typical family man in the 1970s. He had a happy marriage, kids, and a successful career as head accountant at his company. That would all change abruptly when he began experiencing severe headaches in 1975. After consulting with a neurologist, it was discovered that Elliot had a large tumor the size of a fist sitting just behind his eyes. The tumor was pushing on his prefrontal cortex, which is not only responsible for decision making but also for the very essence of who you are. Unfortunately, when the tumor was removed during surgery, much of the surrounding tissue was damaged.

When Elliot woke up, he was a fundamentally different person. He was completely immobilized by every single decision that a person makes throughout the day – what to wear, what to eat, how to organize things, and so on. For instance, when people with healthy brains decide where to eat, we might ask each other what we’re in the mood for. But feelings were of no importance to Elliot when making this decision. He would consider what kind of food a restaurant served, where it was located, how expensive it was, and then he would drive to each one to assess the atmosphere and occupancy. Even after all of this, he still could not decide.

It appeared that the communication between his emotional limbic circuit and prefrontal cortex had been destroyed. Neuroscientist Antonio Damaiso studied Elliot closely and wrote about his apathy extensively. In his book Descartes’ Error, Dr. Damaiso wrote of Elliot, “I never saw a tinge of emotion in my many hours of conversation with him: no sadness, no impatience, no frustration” (Damaiso, 45). Elliot ultimately lost his job, his marriage, and everything else that was once important to him, but it didn’t seem to bother him much.

Cost-benefit analysis and IQ remain intact in these types of patients, but decision making is irrevocably impaired. In an interview at the Aspen Ideas Festival in 2009, Dr. Damaiso explains, “The reason why they can’t choose is because they haven’t got this sort of lift that comes from emotion. It is emotion that allows you to mark things as good, bad, or indifferent, literally in the flesh.” Emotions are what attract us to one thing and push us away from another by making us feel either comfortable or uneasy.

Dr. Damaiso’s work demonstrated that logic alone does not contain the impetus provided by emotion to ultimately choose this over that, thus overturning conventional thought that logic could trump emotion. “Trust your gut” isn’t such mystical advice after all. Your body experiences physical reactions (such as a stomach ache) in response to new stimuli that occurs in part due to memory of past experiences, and then your brain registers the emotion associated with these physical reactions, which influences an ensuing decision. Even when your brain doesn’t consciously remember the details of a past experience, your body and emotional memory remember whether you felt “good” or “bad.”

Where does morality fit into this equation?

We are emotional creatures, but we cannot make reasonable and just decisions when we rely too heavily on emotion. Emotions are a complex product of the brain, body, and environment based on our individual past experiences that influence our morality; they are not the universal dictator of what is moral and what is not.

Morality is what we think and feel is good or bad, right or wrong, whether something causes harm to others or to the self, if it is just or not. It would be wrong to say that our feelings do not play a role in morality – we experience a feeling of disgust or horror in response to things that we believe to be immoral. And this reaction is often a useful evolutionary response: it allows us to make legislation that aims to prevent and/or punish such behaviors so that we can live in a state of order, equality, and fairness.

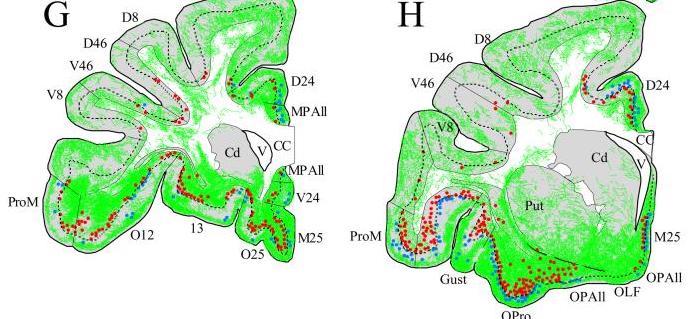

Can the blueprint for morality be found in our brains, or is it something more ethereal? Studies reveal that the insular cortex seems to be heavily involved in one’s morality. This region lights up in response to images that we believe are morally wrong, and we feel disgust: our stomachs churn, muscles tense, and our hearts beat a little faster. The issue is, a similar mechanism occurs in response to something entirely different: novelty, or unfamiliarity. It is not uncommon for our bodies to produce a fear response when we encounter something new or different. Since the insula plays a critical role in evaluating emotions during the decision-making process (especially strong, visceral reactions associated with fear), it will label that uncomfortable experience as “bad,” and so we will probably try to avoid that thing as much as possible. Unfortunately, your insula cannot perfectly parse out what is wrong from what is merely unfamiliar.

It’s no surprise that morality plays a central role in legislative decision-making. To make good decisions, one must utilize both logic and emotion, but depending too much on one or the other is problematic. Too much reliance on logic prevents you from making a decision at all, but relying too much on emotion results in thoughtless, harmful decisions. For instance, a study published in 2020 found that those who relied more heavily on emotion than reasoning were more likely to believe fake news. Believing news that contains false information inevitably influences voting decisions, which can be directly harmful to others. Evidently, over-reliance on emotion can drown out reasoning.

Issues concerning women’s rights, the rights of same-sex people, and the rights of POC are all at stake right now. To some, women’s reproductive rights, gay marriage, and the discussion of Black history in schools is immoral, likely due to an intense bodily reaction (or resistance) to topics that are unfamiliar, and that experience is misinterpreted as “bad.” Religion is almost always used as a justification for this behavior, but what it often comes down to is a misguided response to an evolutionary mechanism that developed hundreds of thousands of years ago to protect us from threats and keep us alive. But we aren’t fighting saber-toothed tigers anymore; immigrants and gay people are not threats.

During a presentation at Stanford in 2017, world-renowned biologist Dr. Robert Sapolsky impeccably captures the dilemma with moral decisions, which he presented alongside images of a Muslim man praying, an interracial couple, a queer couple, a transgender man, a homeless person, and an abortion clinic:

“That’s why if something is sufficiently morally disgusting, we feel sick to our stomachs… we feel queasy. Now this is great because it certainly gives a lot of visceral force to things that we find to be morally appalling. But there’s a problem with this, which, of course, is that one person’s morally disgusting behavior is somebody else’s perfectly normal, loving lifestyle. The trouble with the visceral force of moral disgust is it just begs you to use it as a litmus test to decide, ‘How do I figure out what’s right and wrong in the world? Well, if it seems so different than what I normally do that it makes me feel queasy, then it’s wrong, wrong, wrong.’ And this wisdom of repugnance is a way of making some very bad moral choices.”

We must draw the line between fair, rational morality and emotionally-driven reactions to “the other,” or else we are subject to continue living in a country that strips the rights of millions of human beings in order to make a subgroup of people feel more comfortable.